|

With a wealth of historical detail as a foundation, the old life of

Pompeii has been brought to the screen by Hollywood. The opening credits

note that the story is

original and not related to the novel by Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The

part that the Bulwer-Lytton book played in the construction of this film

had to do chiefly with backgrounds. The characters are entirely different.

The plot and theme bear no resemblance. The picture depicts action and

events that are completely foreign to the novel. With a wealth of historical detail as a foundation, the old life of

Pompeii has been brought to the screen by Hollywood. The opening credits

note that the story is

original and not related to the novel by Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The

part that the Bulwer-Lytton book played in the construction of this film

had to do chiefly with backgrounds. The characters are entirely different.

The plot and theme bear no resemblance. The picture depicts action and

events that are completely foreign to the novel.

The setting is Pompeii, which was at the foot of Mt. Vesuvius on the

Bay of Naples. The time is the first century.

The story concerns Marcus, a happy, peace-loving young blacksmith in Pompeii.

He has everything he wants--a loving wife and

son, good health and money earned at his forge. Abruptly his happiness ends.

His wife and child are run down by a chariot. Both are seriously injured

and Marcus has no money to pay a doctor to treat them. Both his wife and baby die. Embittered,

Marcus feels he lost his happiness because he lacked money. "I've lost all

I loved because I was poor. ... Money is all that matters." He determines to make wealth the aim of his career.

Sacrificing all his ideals, Marcus becomes a professional gladiator. In a year he is champion, idol of

Pompeii. Discovering that one of his victims leaves a six-year-old son, he

adopts the child, Flavius. To tutor the youngster, he purchases an

educated Greek slave, Leaster.

When Marcus is injured too seriously to fight again, he becomes a slave dealer to supply the arena with men for the

games. Finally, discarding all principles, he determines to make himself

head of the arena. The tutor reminds him that he would be responsible for

the slaughter of thousands of slaves. "I mean to get money and I don't

care how."

Marcus plans to go to Jerusalem to buy horses for the chariot races. A fortune teller tells Marcus

to take Flavius with him to Judea, to see the greatest man in Judea.

Marcus thinks she's referring to Pontius Pilate, the governor of Judea,

but she was referring to Jesus.

Unofficially aided by Pontius Pilate, the roman Procurator, Marcus

heads a gang of desperadoes, raiding a desert tribe, taking horses and

treasure.

Marcus presents his son to Pontius Pilate. |

Rathbone as Pilate |

Returning to Flavius, he finds the child dying of injuries received when

thrown from a horse. Frantic, he takes him to a Teacher known to heal the

sick. The child is cured.

Back in Jerusalem, Pontius urges him to take his treasure and leave the

disturbed city. Only that morning the mob had forced him to condemn an

innocent man, a subversive young rabbi named Jesus Christ. Marcus learns that this man is the Teacher who saved

Flavius. Witnessing Christ's march to Calvary, Marcus is moved by his

plight, and he starts to aid him, but love of gold and ambition for the child

overpower him and he passes by. Burbix, head of the gang he had led into

the desert, accompanies him back to Pompeii as friend and aide.

Twenty years pass. Marcus is head of the arena, rich and popular.

Pontius is stopping for Flavius on his return to Rome. With wealth,

intelligence and the patronage of Pontius, Marcus knows Flavius can become

a power in the Empire.

Flavius, grown to manhood, loves his father but is bitterly opposed to

slavery and the arena. Marcus does not realize the great depth of this

hatred; neither does he know that the boy is in love with Clodia, a slave.

Flavius, in spite of his father's insistence that it was a dream, has

always remembered vaguely the Teacher he saw in Judea. Marcus dismisses

the whole notion of Christianity as superstitious nonsense.

Partly in attempt

to follow in the footsteps of this man who taught mercy, partly because of

his love for Clodia, Flavius commits Rome's deadliest crime. He aids

slaves to escape. The group includes Clodia and he take them to a cave in

the hills, planning their permanent escape to an uninhabited island.

The mysterious escape of slaves is becoming a great concern to the

Prefect, especially as Marcus taunts him because he consistently fails to

recapture them. Marcus' interest lies solely in the fact that he needs

more victims for the arena—the fate of runaway slaves.

Pontius arrives but Flavius refuses to go to Rome, saying he wants no

part in ruling an Empire based on slavery. Marcus is bitterly

disappointed, but Pontius assures him that Flavius can come to Rome later

when he gets over his youthful idealism.

Flavius, learning that the Prefect has captured a slave who knows of

the hiding-place, and is torturing him to make him reveal its location,

leaves hurriedly for the cave, urging the slaves to the sea. He is too

late. All of them, including Flavius and Clodia, are captured.

|

Marcus and Pilate discuss Flavius going to Rome. |

Pilate observes Flavius's concern about the slaves. |

The day of the games dawns clear, though an odd cloud hangs over

Vesuvius. Burbix brings news of the capture of the slaves and Marcus,

pleased that the games will now be a success, leaves for the arena.

Leaster, who has been aiding Flavius in his activities, hastens to the

cells, hoping against hope that the boy had escaped. Learning that he had

not, he goes to the arena, bringing word to Marcus that his son is among

those condemned to die. Marcus, in desperation, tries every means to save

him and fails. All his wealth and power mean nothing.

The captives are herded into the arena to face the barbarians. Before

the eyes of Marcus his son is stabbed and goes down.

Then Vesuvius bursts forth. Earthquake follows earthquake. Pompeii

becomes a mass of maddened humanity trying to reach the sea. Before the

onslaught of the fiery volcano, all of the citizens of Pompeii are reduced

to a common level of helplessness.

Leaster is killed trying to save Clodia. Flavius, though injured,

rescues her and the two start for Marcus' private wharf. Believing

Flavius dead, Marcus is swept along indifferent to the confusion. He meets the

faithful Burbix who is forcing slaves to carry Marcus' treasure to the

wharf. In the end Marcus makes the right decisions for the right reasons. Marcus commands them to leave the gold and carry children

instead.

Reaching the wharf, he finds Clodia and, to his joy, Flavius. He puts

them on board a boat. As they cast off the Prefect arrives with his guard

and treasure. He orders the boat to be unloaded to accommodate himself and

the gold. Marcus delays the soldiers long enough for the ship to escape,

but goes down under a spear thrust.

Dying, he sees once more a faint vision of the Teacher. A voice repeats

the promise, "He that loseth his life for My sake, shall never die." Marcus

passes away in peace, as the falling ash slowly covers the ruined city.

Preston

Foster had just suffered his eleventh injury the day we looked in

upon producer Merian C. Cooper's latest screen spectacle. It was a

cinch, which in this instance is not slang, but a saddle cinch that

broke when the two-hundred-pound Foster, wearing an additional

seventy pounds of armor climbed aboard his horse. He suffered a

nasty and painful spill and only by quick thinking escaped being

trampled by another charging horse. Preston

Foster had just suffered his eleventh injury the day we looked in

upon producer Merian C. Cooper's latest screen spectacle. It was a

cinch, which in this instance is not slang, but a saddle cinch that

broke when the two-hundred-pound Foster, wearing an additional

seventy pounds of armor climbed aboard his horse. He suffered a

nasty and painful spill and only by quick thinking escaped being

trampled by another charging horse.

Such accidents are frequent during the

making of any such great spectacle as Last Days of Pompeii. In fact,

the superstitious—and who in Hollywood isn't—regard the presence of

a jinx as an omen of good luck. All big successes, they say, have

been jinxed in production. Strangely enough, the records seem to

prove it.

According to Foster, the mere

wearing of seventy pounds of costume is bad luck. His helmet alone

weighs nine pounds and if you don't believe that is heavy, you don't

need to ask Mr. Foster. Try carrying it around on your own head all

day. When he counts eleven injuries, he is not counting just bruises

and cuts. A brawny bit of a man, standing six feet two, he was badly

battered up during the three months of shooting. We know. We saw the

bruises.

Yet Foster has no complaints. his

starring part of Marcus, humble blacksmith who becomes champion

gladiator and wealthiest man in Pompeii, is one of the most lengthy

in Hollywood history. He is in every scene, almost every set-up.

The story is not an adaptation of

the classic Bulwer Lytton novel of the same name. It is an original

by James Ashmore Creelman and Melville Baker. Screen play by Ruth

Rose. The director is Ernest B. ("Monty") Schoedsack, long and lank

partner of producer Cooper in other ventures (Grass, Chang, Four

Feathers, King Kong).

Both are noted for attention to

historical accuracy and months of research preceded the filming.

Entire sections of the city of Pompeii were painstakingly recreated

from reconstructed drawings based upon the archaeological remains.

Largest of the sets are the Temple of Jupiter—occupying three full

sound stages (30,000 sq. ft.) on the RKO Pathe lot—and the arena, a

giant structure requiring an acre of ground. Yet the greatest

trouble was caused by ancient Roman coffee urns. They look so much

like modern coffee dispensers in use in one-arm restaurants today,

it is feared they may seem an anachronism.

Contrary to popular belief, Pompeii

was destroyed not by lava from the erupting Vesuvius, but by a fine

volcanic ash which, when cooled, hardened to form a horrible tomb.

The complete destruction of the city is best described by the fact

that the ruins remained undiscovered from the First Century to the

year 1594 and systematic excavations did not really begin until

1763. The Hollywood-built Pompeii will be destroyed by the same

means.

Thousands of extras found employment

in the picture, for the Romans owned many slaves and households were

filled with such servitors. There is a record of one Roman owning

4,116. This man, historical accuracy or no historical accuracy, was

not made a character in the story. There must be some limits even in

a million-dollar production. Imagine, the single item of wigs ran to

a total of 8,000 copies.

Other important players in the cast

include Dorothy Wilson, promising English newcomer John Wood, Alan

Hale, who played with a broken foot, young David Holt, Basil

Rathbone, Louis Calhern and Gloria Shea. They wanted to star Preston

Foster, but he refused by saying, graciously, "The entire cast is

too good to star anyone."

—Hollywood, September 1935, p. 36 |

Basil Rathbone plays Pontius Pilate, the Roman who condemned Christ,

with sensitivity and grace. The character transforms from a decadent

politician to a man plagued by questions and doubts with his decision to

crucify Christ and whether or not Christ was worthy of crucifixion.

According to the pressbook for the film, Rathbone believed the lifetime

of Jesus to be the most dramatic period in history. In 1929 Rathbone

appeared in the title role of the play Judas, which he co-wrote

with Walter Ferris. "Because I am so interested in this period, I was

particularly anxious to play Pilate," Rathbone explained, "especially when

I read the part and found it to be one of the best written roles I have

ever played on stage or screen. It is beautifully conceived and deeply

touching. It characterizes Pontius as I feel the man really was—a

political puppet in the hands of Rome. the story of the man who condemned

Christ is a tragedy of helplessness."

Pilate washes his hands after condemning Jesus. |

"What have I done?" |

In a 1937 interview, Rathbone was asked if Pontius Pilate in The Last

Days of Pompeii was a true-to-life character. Rathbone responded:

| Pontius Pilate? Of course he was true to life. You can't call him a

"heavy"! He did his best to prevent the Crucifixion. He was merely

overwhelmed by odds. You and I could not have stood up before such

opposition. Incidentally, I think that that character was one of the best,

if not the best that I have ever portrayed upon the screen. It was only a week's work, and I told my manager that I would not

consider a week's work. Anyhow, he persuaded me to read the script. Well,

before I had read to the end I felt that I was Pilate, and told him to go

ahead and get that part for me. (from "Gentleman Firebrand" by Dick Pine,

Picture Play, September 1937, p. 92)

|

In an earlier interview, Rathbone expressed much more eagerness to get

the part of Pilate:

| As we spoke of the various roles he has played, I

reminded him of his masterful characterization as Pontius Pilate in

The Last Days of Pompeii, which I thought the finest thing he had

done. "Ah, thank you!" he said. "Yes, I think it's the best thing I

have done on the screen, and perhaps the best thing I've done in my

life. When I returned to Hollywood my manager said, 'Basil, they

want you to play Pontius Pilate in The Last Days of Pompeii. It's a

week's work.' I told him I wouldn't even consider a week's work. He

wanted me to read the script, as a favor to him. I got the script

with the part of Pontius Pilate all marked out. As I read it, I had

cold shivers running up and down my spine. I called my manager and

said, 'Bill, I was wrong. Get that part for me whatever you do.' It

was magnificently written, with economy of words—truly a sublime

characterization. I played the part, and the director will tell you that

everything you saw on the screen was the first take. Not because I was a

good boy and learned my lines, or a superlative actor, but because the

part was me, and I was the part." (from "Hissed to the

Heights—That's Rathbone," Motion Picture,

July 1936, p. 74) |

In his autobiography, Rathbone states that he considered The

Last Days of Pompeii to be a "quality" picture. (In and

Out of Character, p. 152)

|

As entertainment, The Last Days of Pompeii is exciting, spectacular and

ennobling in a matter-of-fact fashion. As an actor's Roman holiday, it is

particularly satisfactory for razor-nosed Basil Rathbone. Though deprived of

the peg-topped trousers which have so often added to the elegance of his

impersonations, he makes his Pontius a brilliant prototype of a world-weary

and sardonic early empire politician. The most exciting moment in The Last

Days of Pompeii is not the eruption of Vesuvius but a quiet scene on Marcus'

front porch when Flavius asks Pontius, back from his procuratorship, whether

there was a faith-healer in the province who used to preach the Brotherhood

of Man and, if so, what became of him. Says Pontius Pilate: "There was. I

crucified him."

—Time magazine, October 28, 1935 |

"Basil Rathbone portrays Pontius Pilate with a master's touch." —Robert Tobey, The International Photographer, January 1936, p. 32

"The hero of the occasion is Basil Rathbone, whose Pilate is a

fascinating aristocrat, scornful in his hauteur and sly in his reasoning."

—The New York Times, October 17, 1935

Rathbone as Pontius Pilate |

Marcus and Pilate |

"The film's acting honors go to Basil Rathbone as

Pilate, who transforms from a swaggering young skeptic to a

conscience-stricken old man. On its original release, the film lost 237,000

dollars, but in the long run made a profit via periodic reissues." —Hal

Erickson, Rovi

"Impressive spectacle stuff with plenty of action and several real

thrills ... Cast is excellent." —Independent Exhibitors

Film Bulletin, Oct. 16, 1935

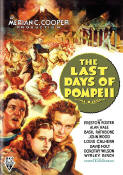

The

Last Days of Pompeii is a picture that should have been filmed in

color. It cries for color. Even in black and white, it is a

spectacular vision, unfolded against a background of the ancient

Roman Empire in all its glory, pomp, and barbarism ... a spectacular

vision with a very human and timeless story in the foreground. For

centuries, people have wondered what life was like in the beautiful,

famed, and fated city of Pompeii, doomed to destruction by a

volcano. Here is a graphic, imaginative answer. The principal

character is an ironic gladiator, a public hero, who sells his soul

for gold—magnificently played by Preston Foster. As his adopted

child who redeems him, David Holt tears hearts loose from their

moorings. And only a little less memorable are John wood, Dorothy

Wilson, Basil Rathbone, Alan Hale and Gloria Shea. The

Last Days of Pompeii is a picture that should have been filmed in

color. It cries for color. Even in black and white, it is a

spectacular vision, unfolded against a background of the ancient

Roman Empire in all its glory, pomp, and barbarism ... a spectacular

vision with a very human and timeless story in the foreground. For

centuries, people have wondered what life was like in the beautiful,

famed, and fated city of Pompeii, doomed to destruction by a

volcano. Here is a graphic, imaginative answer. The principal

character is an ironic gladiator, a public hero, who sells his soul

for gold—magnificently played by Preston Foster. As his adopted

child who redeems him, David Holt tears hearts loose from their

moorings. And only a little less memorable are John wood, Dorothy

Wilson, Basil Rathbone, Alan Hale and Gloria Shea.—Movie Classic, December 1935, p. 51 |

Hollywood took some liberties with the chronology of historical events

to tell this story. Jesus died around 35 AD. In the film, Pontius Pilate

visited Marcus in Pompeii twenty years later (which would have been about

55 AD)

and Vesuvius erupted shortly after Pilate left for Rome. In fact, Vesuvius didn't

erupt until 79 AD. Little is known about Pilate's life after the death of Jesus.

We know that he left his post in Jerusalem and returned to Rome in 36 AD.

Tradition holds that he was so consumed by grief that he took his own

life, but there is no evidence to suggest how Pilate died.

Lavish sets, reproductions of the ancient city, were built to stage the

spectacle. These included the great Forum and the Temple of Jupiter,

streets, shops, the slave market, the giant arena, wharves, and private

homes of classic beauty.

More than a year of research by many trained men and women was required

to insure absolute accuracy in the construction of these settings. This

investigation included the exhaustive examination of books, photographs,

drawings and architectural reproductions, relating to Pompeii. In addition

to this work, Merian C. Cooper, who produced the film, visited the

ruins of Pompeii, gathering information about the city.

Pilate and Marcus meet for the first time in Jerusalem. |

Pilate and Marcus meet 20 years later in Pompeii. |

At the RKO Radio studios massive motion picture sets were built into

accurate reproductions of the classic city. One is the Pompeiian Forum and

its famous Temple of Jupiter, seat of pagan rites. It required one hundred arc lights to illuminate this setting. The

operating crew numbered 120, 40 of these being electricians. About four

hundred extras were used to stage the scene of festival.

Another setting is the

beautiful home of Marcus, hero of the photoplay — a rich man's marble

palace of great halls, graceful pillars, beautiful gardens where fountains

play, and rich furnishings. There is also the mammoth amphitheatre arena,

guarded by a mighty colossus, through the straddled legs of which went

hosts of men into the arena on their way to doom. These monuments of pagan

splendor, however are smashed to fragments during the convulsive scenes of

the picture's climax, which depicts the debacle resulting from an eruption

of the volcano Vesuvius, a triumph of special effects.

THE LAST WORD IN

SPECTACULAR PRODUCTION GORGEOUSLY PRODUCED AND ACTED WITH INTENSELY

HUMAN STORY.

Easily one of the Ten Best of this or

any other season. It makes all other spectacular productions fade in

comparison. The mob scenes are magnificently handled. The scenes in

the arena of Pompeii are stupendous and awe-inspiring. And for the

climactic smash, the eruption of Vesuvius followed by earthquakes

with thousands of people fleeing from the arena has never been

equaled for sheer magnitude and spectacular smash and perfect

detail. It's a dramatic triumph of impressive magnitude. Combine

this with an emotional and very human story consummately acted, and

you have a screen spectacle that will have the entire community

talking. Preston Foster plays the role of a blacksmith who becomes a

gladiator in the arena, and when his wife and baby die from an

accident, he is embittered and resolves to attain vast wealth and

power. He adopts a boy, son of one of his arena victims, and his

entire life is centered about the young man as he grows up. The

climax in the arena as the son espouses the cause of the slaves and

the father tries to save him from death, followed immediately by the

eruption of Vesuvius, is an unforgettable screen experience that

twill linger in memory. Everything about the production is superb—musical

score, photography, directing, acting.

—The Film Daily, Oct. 3, 1935, p. 8 |

"A stupendously big production, handsome and spectacular ... Exciting,

packed with action ... Don't miss it." —New York Daily Mirror

"A masterpiece of screen realism." —New York Post

"Elaborate spectacle ... filmed on a large and lavish scale." —New York Evening Journal

"Effective screen spectacle" —New York Herald Tribune

"Persuasively staged and excitingly narrated." —New York Times

"A glorious film." —Boston American

The young Pilate and his servant |

Marcus and Pilate |

"Has as much of story as it has of spectacle." —Boston Transcript

"Big spectacle ... lavish screening." —Boston Post

"Exciting enough to satisfy anyone." —Boston Record

"A notable achievement." —Cincinnati Times Star

"An absorbing show." —Cincinnati Enquirer

"Life of pagan city depicted in mighty spectacle." —Cincinnati Post

Dramatic Spectacle

Spectacular in story quality and production value this isa picture to

stir the minds of exhibitors and patrons alike. A massive feature,

reflecting in every phase the care, thought and diligence put into it

by producers, director, and players, it is screen merchandise of a

caliber that should inspire the most extraordinary showmanship in

order that commercial returns which its entertainment value more than

justifies should be returned.

As the title indicates, "The Last Days of Pompeii" sets its time as

that of Christ's last years on earth and the early part of the

Christian Era and establishes the locales as ancient Rome, Judea and

Pompeii, and this likewise establishes it as a costume picture. But

whether costume or not, together which the production features—the

gladiatorial combats reflecting the almost inhuman decadence of a

pagan race, the cruel sports of the Colosseum, the atmospheric

presentation of the Crucifixion, or the vivid manner in which its

picturization of ancient racketeering parallels the most flamboyant of

modern gangsters—it tells a story of

human drama which from the point of view of power of theme and

emotional impact is as attention arresting as the most moving current

happenings. The cataclysmic eruption of Mount Vesuvius and the earth

shattering destruction, which climax all the previous spectacles,

seldom if ever have been duplicated on the screen either.

Bare of the wealth of substantiating

production detail, awe inspiring features which lend great power to

the motivating story, "Pompeii" is drama. It's the drama of Marcus, a

tragedy embittered man, who came to believe that only in the

possession of money and power could happiness be found, of a merciless

gladiator of the arena, champion of champions, who in glory found

solace in the adoption of a boy to replace his dead child.

Climbing the ladder of success, he

becomes a promoter, allying himself with Pontius Pilate. He becomes a

slave trading racketeer providing the human fodder to satisfy the

depraved tastes of the roaring arenas. In Jerusalem, he hears of a

great Teacher, a man who believes in meekness, kindness and humility,

the direct antithesis to the character he is. His son being injured,

Marcus again knowing a fear that once chilled his soul, he takes him

to the Teacher. the boy is healed. Then follows the drama,

atmospherically presented, of Calvary.

Years pass. Marcus, now the most

important influence in the Roman empire, knows that his association

with Pilate can do much for his son Flavius, now grown to manhood. But

a different spirit motivates Flavius' life. He has never forgotten the

presence of the martyred Teacher. In love with one of his father's

slaves, Claudia, Flavius becomes an enemy of his father. He makes it

possible for the slaves the escape. This wild horde threatening the

very existence of Rome, the dramatic situation is menacing and is made

more so when Flavius actually casts his lot with them. But the power

of Roman arms is not to be denied. The slaves, Flavius and Claudia

among them, are to be massacred for the delight of the mob. Marcus

sees his son go down in the onslaught. Then the volcano erupts. Lava

pours down on the ruins of Pompeii that earthquakes have razed. In the

thrilling climax, Marcus with the words of the Teacher ringing in his

ears helps Flavius and his bride Claudia to escape, he himself dying.

In every way this is a big picture,

rich in all the necessities required by any type of showman to satisfy

the demands of his patrons. There's a story to sell and there's

amazing production to help make the appeal of that story more

impressive. The strength or weakness of cast names—and the

personalities presented are worthy of anyone's best efforts—is of

little comparative significance. All that is needed is a sincere

effort to convince the public of the show's worth, a matter for which

all the essentials are provided.

—McCarthy

—Motion Picture Herald, Oct. 12,

1935, p. 40

|

"Gives seekers after thrills something to remember." —Denver Post

"You'll want to see it." —Denver Rocky Mt. News

"Will startle the motion picture public." —Washington Star

"A gigantic spectacle ... magnificent in scope." —Washington Times

"Hits a new high for sensationalism." —Washington Post

"A magnificent achievement." —Washington Herald

Basil Rathbone and John Wood |

Preston Foster, Basil Rathbone and John Wood |

"Colorful, exciting, and building toward a smashing climax." —Washington

News

"Powerful film." —San Francisco Examiner

"Will be talked about for weeks." —San Francisco News

"A vivid spectacle." —San Francisco Call-Bulletin

"Superb entertainment." —San Francisco Chronicle

As

a spectacle, this production rates high in the month's ratings. As

out-and-out dramatic fare, it is still above the average, although we

believe the photographers and the technical department are the real

stars of the picture. Sets are gorgeous, and the scenes of the

destruction of Pompeii are actually breath-taking in their seeming

reality. For those scenes alone the picture can be highly recommended.

The story is not the tale we all know, for the producers have taken it

upon themselves to make a complete change in that department. We now

find "The Last Days of Pompeii" to be a story of a poor young

blacksmith (Preston Foster) who decides, after his wife and son die,

because he has no funds for their proper care, that money and power

shall be his gods. He attains hi ends only to find everything he has

built up shattered before him, and the real truth coming to him. An

excellent cast is headed by Basil Rathbone, David Holt, Louis Calhern,

John Wood and Dorothy Wilson. As

a spectacle, this production rates high in the month's ratings. As

out-and-out dramatic fare, it is still above the average, although we

believe the photographers and the technical department are the real

stars of the picture. Sets are gorgeous, and the scenes of the

destruction of Pompeii are actually breath-taking in their seeming

reality. For those scenes alone the picture can be highly recommended.

The story is not the tale we all know, for the producers have taken it

upon themselves to make a complete change in that department. We now

find "The Last Days of Pompeii" to be a story of a poor young

blacksmith (Preston Foster) who decides, after his wife and son die,

because he has no funds for their proper care, that money and power

shall be his gods. He attains hi ends only to find everything he has

built up shattered before him, and the real truth coming to him. An

excellent cast is headed by Basil Rathbone, David Holt, Louis Calhern,

John Wood and Dorothy Wilson.

Research on this picture took longer than any yet undertaken by RKO

Studios. For a year and a half, experts waded through material on the

ancient days of Pompeii, on costumes and customs of the people, and

particularly on the architectural developments of the time. Merian C.

Cooper, the producer, took a special trip to that part of the globe

where Pompeii formerly stood, in order to give it a first-hand

once-over and capture the mood of the place. The magnificent sets

which were built on the studio lot were beautiful enough for permanent

buildings but were wrecked in order to show the final scene of the

smoking ruins. The last scene in the picture is an exact replica of

the famous painting from which the film takes its name. On the sets

were reproduced the Temple of Jupiter, the market and forum, a section

of the Arena with 75-foot statues surrounding it, a shopping section

of the city, with the potters' shops, silversmith's stores,

wine-shops, etc. There were also built on the lot two houses typical

of that time. They were complete in every detail with the rooms

opening off a central courtyard as in the good ol' days. Props for

this picture ran up into Big Money. For wigs alone, $8000 was spent,

to say nothing of the cost of hundreds of suits of armor, chariots and

costumes.

—Modern Screen, December 1935, p. 10 |

Other films were produced with same title, The Last Days of Pompeii, but different plots

in 1908,

1913, 1926, 1959, and 1984.

Pilate meets with Marcus immediately after condemning Jesus. |

Pilate shares a meal with Marcus and the Prefect (Louis Calhern)

in Marcus's home. |

See Page Two for pictures of posters,

lobby cards and promo photos.

.

|

Cast |

|

| Basil Rathbone

... |

Pontius Pilate |

|

Preston Foster ... |

Marcus |

|

Alan Hale

... |

Burbix |

|

John Wood

... |

Flavius (as a man) |

| Louis Calhern

... |

Prefect |

|

David Holt ... |

Flavius (as a boy) |

|

Dorothy Wilson... |

Clodia |

| Wyrley

Birch... |

Leaster |

|

Gloria Shea

... |

Julia |

|

Frank Conroy

... |

Gaius |

| William V. Mong... |

Cleon |

|

Edward Van Sloan... |

Calvus |

|

Henry Kolker

... |

Warder |

|

Murray Kinnell

... |

Simon, Judean Peasant |

|

Zeffie Tilbury ... |

the Wise Woman |

|

John Davidson ... |

Phoebus, runaway slave |

|

Ward Bond ... |

Murmex of Carthage, gladiator |

|

Curley Dresden ... |

Cato the Gladiator |

|

John T. Murray ... |

Pilate's servant |

|

Cliff Lyons ... |

Ostorius, a gladiator |

| |

|

|

|

|

Credits |

|

| Production

Company ... |

RKO |

| Producer

... |

Merian C. Cooper |

|

Director ... |

Ernest B. Schoedsack |

|

Screenplay ... |

Ruth Rose and Boris Ingster (based on a story by James Ashmore Creelman and Melville Baker) |

| Cinematographer

...

|

Eddie Linden, J. Roy Hunt, and Jack Cardiff |

| Film Editing

... |

Archie Marshek |

|

Music Director ... |

Roy Webb |

|

Composers, stock music ... |

Bernhard Kaun, Max Steiner |

|

Sound Effects ... |

Walter Elliott |

| Art Director

... |

Van Nest Polglase |

| Set

Dresser

... |

Thomas Little |

|

Costumes ... |

Aline Bernstein |

|

Makeup Artists ... |

Robert J. Schiffer, Howard Smit |

|

Special Effects ... |

Willis O'Brien, Vernon L. Walker and Harry Redmond |

|

Asst. Director ... |

Ivan Thomas |

| |

|

|

|

|

The Last Days of Pompeii is available on DVD

|

|