East of SuezA play in seven scenes by W. Somerset Maugham. Opened at His Majesty's Theatre, London, September 2, 1922. After 209 performances, the play closed on March 3, 1923. Staged by William Abingdon; produced by Basil Dean. Proprietor: Joseph Benson; Presenter: George Grossmith, J.A.E. Malone; Asst. stage manager: James Jolley; Box office manager: Hollingshead; Manager: Carl F. Leyel; Music: Eugene Goossens Jr.; Music director: Percy Fletcher; Chinese music conductor: Chang Tin; Costume design, Props design, Scenery: George W. Harris; Scene builder: Brunskill, Robinson; Scene painter: Philip Howden; Costumes: Elspeth Phelps, Bradley's, Hyman, Reandean Wardrobe, Burkinshaw and Knights; Perruquier: William Clarkson; Electrician: T. J. Digby

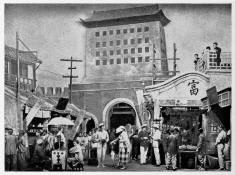

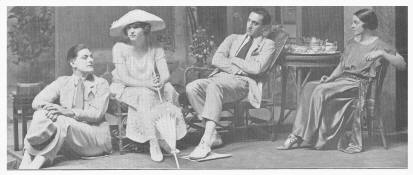

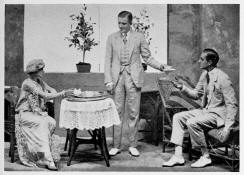

The following plot summary, written by B. W. Findon, is adapted from the souvenir program for the play: Mr. Maugham has divided his story into seven scenes, with two definite intervals, but two of the scenes are picturesque representations of life as it can be seen by the tourist in a city such as Peking, which serves as a highly-coloured background for the tragic episodes that provide the meat in the author's plot. The first scene depicts street life in Peking, just before nightfall, and the other, a wedding procession passing in the rear of the apartments of Harry Anderson and his Eurasian wife; there is another "set" typical of the Orient, in which the Amah is seen invoking the aid of Buddha in the Temple of Fidelity and Virtuous Inclination, which adjoins the Anderson's dwelling place. The play opens with a conversation between Harold Knox, George Conway,

and Harry Anderson on the difficulties that occur in marriages between

Europeans and half-castes, and the two former are very awkwardly placed when

Anderson informs them he is about to marry a beautiful Eurasian, and that he

has invited her to tea in order to be presented to his two friends. When she

arrives, it is seen that George Conway and Daisy are acquainted, and George

is confronted with an awkward problem, for he had been Daisy's lover, and

was only prevented from marrying her through fear of losing his position in

the British Legation at Peking. Daisy had then gone to Singapore with an

American, after which she had been sold by her mother to a Chinaman, Lee Tai

Cheng, under whose care she lived in Shanghai. Acting on the principle that

silence is golden, George says nothing of Daisy's past to his friend. The

curtain goes up on the next scene when Harry and Daisy have been married a

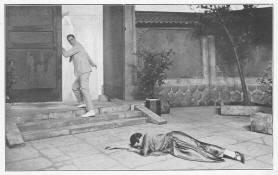

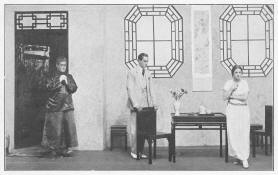

year. It is obvious the union has not proved an unqualified success; Daisy is discontented; Harry has realised that his marriage has resulted in social ostracism; he tells Daisy that at his own request he has effected an exchange to a station in the interior where there would be no white element to count. But Daisy refuses to go, and we quickly learn that George Conway is the reason why she desires to remain in Peking. She is tired of her husband, and there is a wild desire on her part to resume her old relations with George. Lee Tai Cheng has followed Daisy from Shanghai, and is leaving no subtle means untried to regain possession of her. He makes an insidious proposition that she shall poison her husband, and then a plot is concocted between him, the Amah, and Daisy, whereby a man shall be attacked just outside the Andersons' apartments, his call for assistance will be answered by Harry, who will rush out and be stabbed to death in the melee. The Amah unloads Harry's revolver, and all works according to plan, except that the first to rush out is George, who receives the assassin's dagger in his lungs. Harry suspects foul play, and that the Amah is at the bottom of it; he will have her leave the house, and then it is that his wife makes the dramatic avowal that the old hag is her mother. George has received an ugly wound, but with good care and attention he is speedily on the way to convalescence, and his nurse and helpmate on the road is Daisy. In the weeks that ensue, there is the development of the love interest between Daisy and George, until his soul revolts at the injury he is doing his friend, and at all costs he would bring the liason to an end. Lee Tai Cheng is still pursuing his design to regain Daisy, and to hasten matters he tells her that George is engaged to a young English girl, sister to Harold Knox. All the tigerish instincts in the woman are aroused, and in her fury she hands him George's letters to send to her husband, who is on business up country. In a passionate scene between Daisy and George, she accuses him of treachery towards her in engaging himself to the English girl; she is overwhelmed with remorse when he tells her that there is no truth in the story, and her anguish is intensified when he would leave her and the country; it is then she tells him that his love letters have been sent to her husband, and of her own hope that a divorce will ensue so that she and he can be married. Daisy has not foreseen the way that George would view her avowal, the torture of the man when he realised that the friend who trusted him, his old schoolfellow, would know of his perfidy; the situation is beyond his power of endurance; he cannot face the man whom he has betrayed; he goes into the next room, locking the door behind him, and then a shot tells the end to the distracted woman. Following George's suicide, Daisy gives up her attempts to be a European and returns to native dress and habits. When her husband returns, he finds her sitting impassive, clothed in a Manchu dress, to symbolise, we may assume, that China takes back its own.

On July 26, 1922, The France sailed from New York to London with Basil Rathbone on board. He had been in New York, starring in The Czarina, which ended its run on Broadway in May 1922. When he landed the part of George in East of Suez, Rathbone sailed to London to start rehearsals. The play opened in London on September 2, 1922, and in New York (with a different cast and crew) on September 21, 1922. As a result, East of Suez was playing simultaneously in the two cities. In the London cast, Norah Robinson succeeded Meggie Albanesi in the role of Daisy in January 1923. She continued in that role until the play closed on March 3, 1923. Of producer Basil Dean, Rathbone wrote, "He had a way of treating his actors as if they were trained animals. He cracked the whip and when he so did we were expected to jump. His was hardly an endearing personality. But he produced successful playsand this was a factor no actor could afford to ignore." (In and Out of Character, p. 52) The Actors' Association raised questions and objections to the employment of about sixty Chinese rather than English extras for the crowd scenes in East of Suez. At a time when thousands of British players were suffering hardship through unemployment, it was hard to see so many foreigners earning a weekly paycheck. Management claimed that only Chinese actors, speaking Chinese, could give authenticity to a scene such as the Chinese marketplace in Peking. Their engagement was essential to give effects that could not otherwise be obtained. Basil Dean, the producer, stated that if he couldn't engage the Chinese, he would cut their scenes from the play, even though that would weaken the play. He believed that English extras could not create the correct atmosphere, and would ruin the play. The Era (September 13, 1922) stated the opinion that "in employing aliens in their company they [management] are violating none of the terms of their agreement with the Actors' Association and breaking none of their rules. In the first place, the Chinese in East of Suez are supernumeraries, and supernumeraries do not come within the scope of the Actors' Association. ... For the A. A. to demand the substitution of their members for the Chinese at His Majesty's would be to begin a crusade against the employment of any other than British actors on the stage."

Modern playgoers would likely be appalled by the racism and prejudice evident in East of Suez. Basil Rathbone's character George expressed the common prejudices of the early twentieth century, saying, "Somehow or other they [Eurasians] seem to inherit all the bad qualities of the two races from which they spring and none of the good ones. I'm sure there are exceptions, but on the whole the Eurasian is vulgar and noisy. He can't tell the truth if he tries." As if that wasn't bad enough, the Amah's pidgin English makes us cringe. For example: "You make missy cly. You velly bad man. ... What for he tell me no listen? So fashion I sabe he say something I wanchee hear. He wanchee you leave Peking." Yikes! Yet the pidgin English didn't bother any of the contemporary theatre critics. They all praised Marie Ault and her interpretation of the Amah. Of course, in 1922 racial sensibilities were not what they are today. Although we may object to the use of terms such as half-caste and Chinaman, they were acceptable terms when this play was produced. Maugham didn't intend to offend; he was reflecting his reality. I don't think that Maugham was trying to make a point about racism. He was telling the tragic love story of Daisy and George against the exotic backdrop of China in the British colonial period. Some may also find the Asian stereotypes offensive, as well as seeing a Caucasian actor playing a Chinese character. (Remember Swedish actor Warner Oland as Detective Charlie Chan?) Although the producers used Chinese actors as extras, the main characters of Wu, Lee Tai Cheng, the Amah, and Daisy were played by English actors. And then there is the double standard of what the English deemed acceptable. Harry, a white man, thought it was fine for him to marry Daisy, a woman of mixed race. But when Daisy wanted to socialize with a white woman who had married a Chinese man, Harry was horrified. He said, "Oh, my dear, she was Heaven knows what she was. She's married to a Chinaman. It's horrible. She's outside the pale." Damn that double standard! If we can accept the context in which the play was written, and look past the jarring and derogatory terms, we might be able to enjoy reading it. "Maugham's choice of having the protagonist as half-caste is significant, because then he also deals with the first-hand experience of these prejudices and explores the question of self-identity. The simplistic picture presented by the Europeans is skin deep. Through Daisy, Maugham looks at the internal conflict of a person of mixed race. Maugham seems to be saying that racial memory is so strong that one can never be totally rid of its influence." Analysis of East of Suez (1922), My Maugham Collection, April 17, 2017

In Scene 2, the character Daisy is introduced as "Mrs. Rathbone." Her fiancι Harry believed her to be the widow of Mr. Rathbone, an American businessman. It is likely a coincidence that Somerset Maugham used that name, but it made me chuckle when reading that Basil Rathbone's character George asked Daisy, "Who was this fellow Rathbone?" Here is a portion of their conversation in Scene 2, when they are alone and George questions Daisy about marrying Harry. GEORGE: How can a marriage be happy that's founded on a tissue of lies? DAISY: I've never told Harry a single lie. GEORGE: You told him you hadn't been happily married. DAISY: That wasn't a lie. GEORGE: You haven't been married at all. DAISY (with a roguish look): Well, then, I haven't been happily married, have I? GEORGE: Who was this fellow Rathbone? DAISY: He was an American in business at Singapore. I met him in Shanghai. I hated Lee. Rathbone asked me to go to Singapore with him, and I went. I lived with him for four years. Daisy returned to China after Rathbone died. In his Introduction to Collected Plays, Vol. V (1934), Maugham says of this play: "East of Suez purports to be a play of spectacle. I had long wanted to try my hand at something of the sort, and a visit to China presented me with an appropriate setting. The bare bones of a story that I had for twenty years from time to time turned over in my mind recurred to me. It seemed very well suited to my purpose. I kept my ears open, and from this person and that heard little incidents that fitted in with my scheme and gave it the fullness, colour and variety that it needed. For the first and only time in my career as a dramatist I wrote the scenario which the professors of play-writing teach their pupils to do. It is a practice in which I have always felt there is great danger. For one thing, it is very difficult to hold in the mind's eye the whole development of a play; the imagination (mine, at least ) provides you only with the important scenes, the beginning, the curtains of the acts, and the end; it leaves out the necessary scenes of transition, the scenes of preparation, and the scenes necessary to the mechanism of the play; these passages will in a scenario generally be set down perfunctorily, to make it coherent, and when you come to write your play you will very likely find that the fact of having written them down cramps you. Having forced your imagination to work by an effort of will, it fails than to work with proper freedom. It seems to me better to keep your general idea in your head, with your theme and your chief scenes fluid, as they must be before they are set down in black and white, and trust to the natural development by which, if you have the dramatic instinct, one scene leads to the next. A scenario seems also to paralyse the amiable and useful little imp that dwells in your fountain pen and does for you all your best writing. The prudent writer gives him his head, and if the little fellow has a mind to write something quite different from what he intended, knows that it is only common sense to yield. After all, it is to this wily sprite that is due whatever merit the ignorant ascribe to the unimportant instrument who holds the pen. but the story of East of Suez was so complicated that I thought it necessary to construct a very detailed scenario. I must admit that it made the subsequent writing an easy matter. In a play of this sort, in which exotic and beautiful scenery is used to divert the eye and crowds to give movement and colour, it is evident that the spectacle should be an integral part of the theme. Looking back, I realise that in my inexperience I did not always adhere to the canon, and in this edition I have omitted a marriage procession which I inserted because I thought the common sight in a Chinese city picturesque and amusing, but which had nothing to do with my story. On the other hand, I cannot think that anyone who saw the play will have forgotten the thrill and strangeness of the mob of Chinese, monks and neighbours, who crowded in when the wounded man was brought in after the attempted assassination in the fourth scene. With their frightened gestures and their low, excited chatter, they produced an effect of great dramatic tension."

"Mr. Somerset Maugham seems to have set out to prove the truth of Kipling's axiom 'East is East and West is West. And never the twain shall meet,' for that is the moral of East of Suez, at His Majesty's." The Sketch, 13 September 1922 "This is a good stage play, something more than melodrama, something less than tragedy or comedy. It has distinction, like all of Mr. Somerset Maugham's work. One of his virtues (perhaps the greatest ) is that he handles his situations honestly, and goes through with them." Ashley Dukes, The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 9 September 1922 "The principal roles are played by Basil Rathbone, C. V. France, and Miss Meggie Albanesi, all of whom brilliantly sustain their reputations in what must be to them very unfamiliar environments. The verdict of the audience was markedly favourable." Western Mail, September 5, 1922 "Mr. Basil Rathbone, as the young diplomat with a nice sense of honour, acts with much vigour and charm." The Bystander, September 20, 1922 "Basil Rathbone is excellent as the member of the Embassy." Variety, September 29, 1922

"East of Suez has a connected story, founded on a love romance in China between two English officials and a half-caste with a past, and at times presents thrilling melodramatic features." Dundee Courier, September 4, 1922 "The story has been handled with considerable skill and the play is admirably staged. ... The play promises to be a popular success." Western Morning News, September 4, 1922 "The scenes with Conway, an ungrateful role handled very ably and not without sympathetic touches by Mr. Basil Rathbone, were played especially well by this brilliant young actress [Meggie Albanesi]." The Stage, September 7, 1922 "Miss Albanesi ... outtops most of the young actresses who are her contemporaries. Hers is the emotional triumph, as Miss Ault's is the comic one, at His Majesty's. There is other good workfrom Mr. Basil Rathbone as lover; Mr. Malcolm Keen as the husband; and Mr. C. V. France as the sinister Chinaman." The Illustrated London News, September 9, 1922 "Mr. Somerset Maugham's play, a sort of Far Eastern 'Mrs. Tanqueray,' is quite a good one, and it is excellently acted. I was not quite convinced that an actress of Miss Meggie Albanesi's delicacy of method ought to have been cast for so exacting a part in so large a theatre, but she came through her arduous task very well. On the English side of the cast Mr. Basil Rathbone and Mr. Henry Kendall were good, while on the Chinese Mr. C. V. France and Miss Marie Ault both gave extremely interesting performances." Truth, September 13, 1922

In a 1940 article, Basil Rathbone shared this story: "I remember one time in London when Somerset Maugham was given an assignment to do a play within a period of six weeks. A week later he informed his producers that he was sorry, and returned their check. He simply found that he could not work when he was bound by a time limit. the producers accepted his refusal as gracefully as possible, although they tried to persuade him to continue. About a month later he gave them their play. Without the feeling that he was meeting a deadline, without the fear in the back of his mind that he was going to be late, the play wrote itself. And it was excellent. I played a role in it myself. It was called East of Suez." ("Star Behind the Camera," Popular Photography, March 1940) Film version: Directed by Raoul Walsh, the play was filmed in the USA by Famous Players-Lasky in 1924. A contemporary review says it strays a long way from the original and has a different ending, in which Harry dies and George and Daisy go back to England together. Have a desire to read the play yourself? Here is a link to an e-book: https://archive.org/details/SomersetMaughamEastOfSuezplay Listen to the music that Eugene Goossens composed for East of Suez: https://youtu.be/fj-XD1OLFlI. According to Basil Dean, Eugene Goossens was inspired by the tunes he heard being played in London's Chinatown.

|

_small.jpg)